ROM Being Legendary

“Quantum physics is only now catching up to what our Elders have long understood”

Sieara and I peruse the grand halls of the Royal Ontario Museum, admiring every object encased in the freshly polished glass.

Artifact as art is a movement I hold in the highest regard, when artists work with the archive there is an inherent commentary on how collecting and interpreting material culture can be harmful and rampant with distortions. You see a horned dinosaur skull, I see the team of researchers, archeologists, and curators who brought it here, and I wonder why and for who?

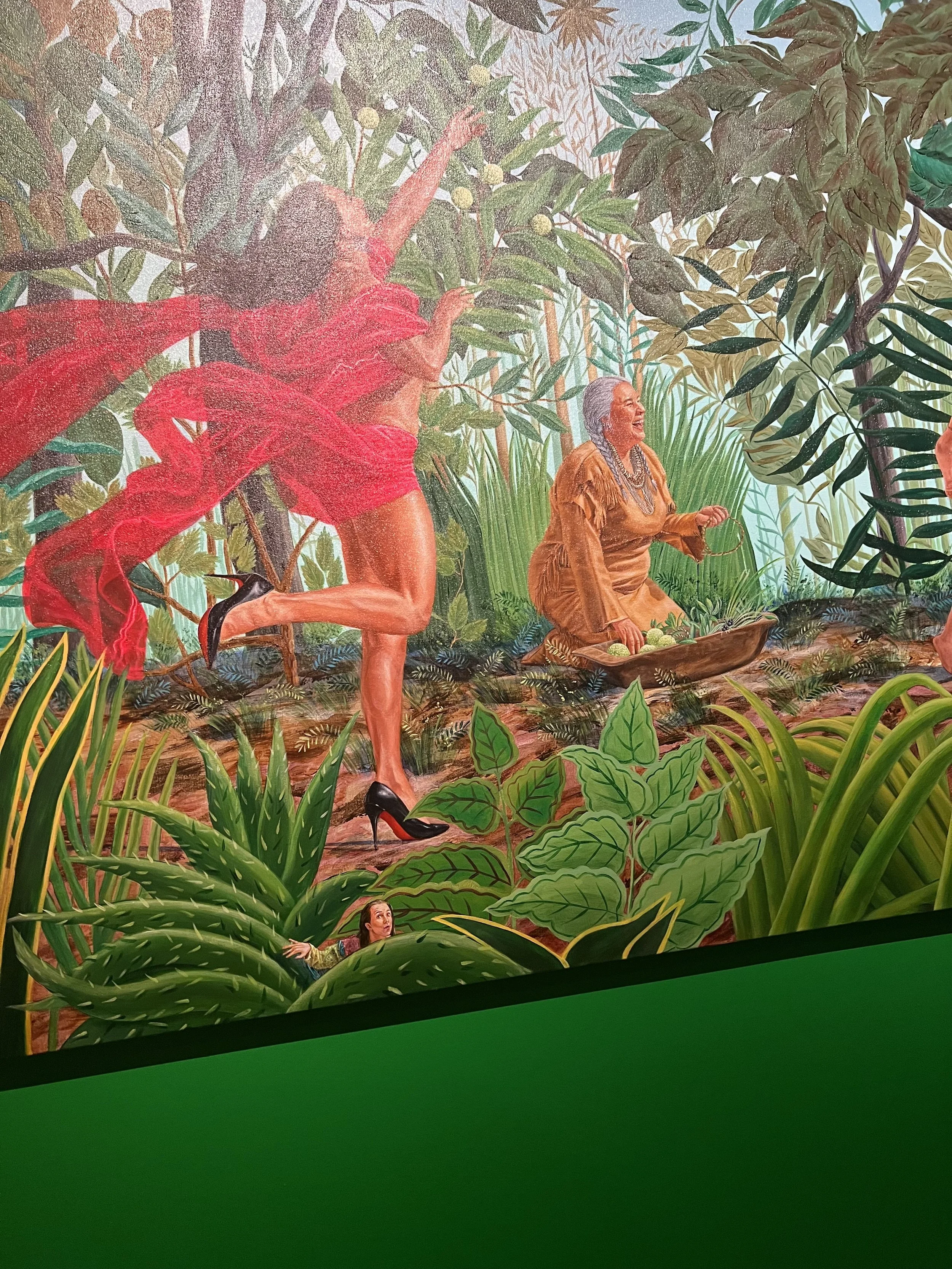

I had previously seen Kent Monkman’s work at the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery in 2017 in an exhibit entitled The Four Continents. Monkman’s attention to contemporary struggles in relationship to historic pains shows a deep caring for the state of the social, environmental, and metaphysical worlds. His intertwining of comedic drama with the unsavoury reality of colonial violence upon Indigenous peoples shines brilliantly, blasting through the cages of my patriarchal-colonial upbringing. As a member of Fisher River Cree Nation, Monkman turns Western European and American art conventions on their heads, and kicks them in their a**es.

In Being Legendary, Monkman intervenes in not only Western European painting motifs but also ethnographic methods of collecting, falsely interpreting, and displaying Indigenous material culture (and bodies). Monkman’s gender-fluid alter ego Miss Chief Lady Testickle takes on a leading role in the artist’s queering of colonial narratives.

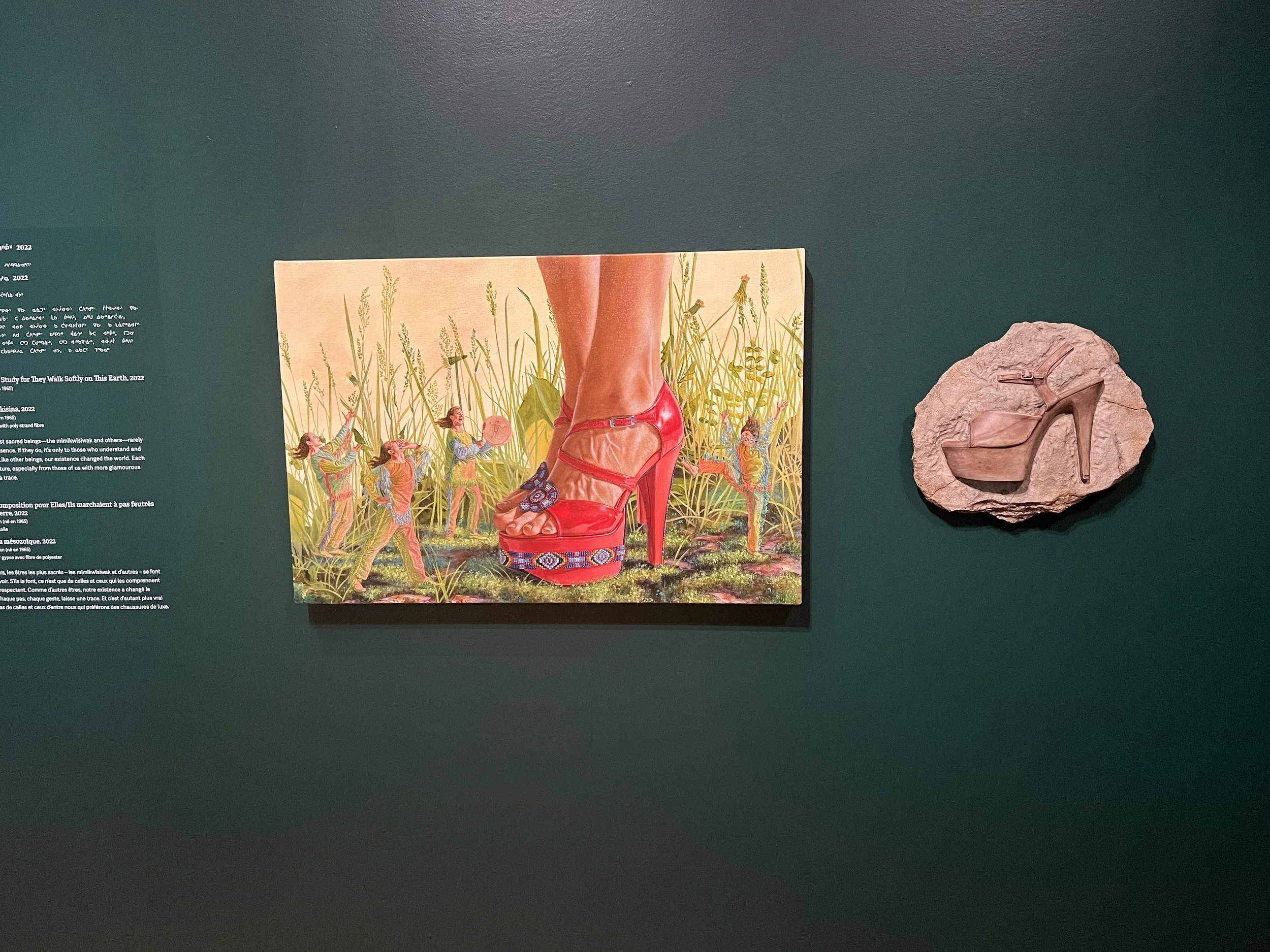

An early point in the exhibition found me standing between the skull of a horned dinosaur skull and a painting of an open-toe-heeled foot surrounded by, in comparison to the manicured foot of Miss Chief Lady Testickle, ant-sized figures. A “fossilized” platform stiletto hangs next to the painterly equivalent to a “foot pic”. Monkman’s diptych display of a prehistoric object to his paintings feels as though he is writing his own history, using authentic and manifested artifacts to challenge, if not fully reject, the histories told by colonial historians.

I was impressed by the interpretive panels throughout the space, written in three languages, Cree, English, and French, they shared Monkman’s feelings about themes of coloniality and his intentions to connect audiences to the figures and voices embedded in the land, and thus to everything that needs to be known.